Mr. Wright Goes to Boston

After spending 41 years in prison for a murder he said he did not commit, Edward Wright joined advocates in Boston to call for an end to wrongful convictions

Edward “Eddie” Wright said he grew up trusting in the legal system. But in 1985, the unthinkable happened: He was convicted of murdering his friend, a crime he said he had nothing to do with.

“It was just like getting punched in the face,” Wright said. “I was disoriented, confused. I couldn’t believe that they found me guilty. I thought that the jury would see through the lies that were being told. I thought I was going to go home.”

Wright was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. But in April, a judge overturned Wright’s conviction, finding that Hampden County prosecutors withheld key evidence and a Springfield detective “knowingly misled the jury” by giving “blatantly false testimony.” And on Wednesday, after spending 41 years behind bars, Wright joined his lawyers and other advocates outside the Massachusetts State House for Wrongful Conviction Day—an annual event aimed at raising awareness about how such tragedies occur, how they can be prevented, and how to compensate victims.

“We are thrilled that Eddie is here marching with us in person today,” said Stephanie Hartung, a lawyer with the New England Innocence Project who represented Wright. “For many years, on Wrongful Conviction Day, we spoke Eddie’s name. We had a poster with his photo. We held it up as a reminder of his and so many others’ struggle for freedom.”

Wright is one of 100 people who were exonerated after being convicted of a crime in state or federal courts in Massachusetts since 1989, according to data from the National Registry of Exonerations. Throughout the country, a total of 3,737 have been exonerated since 1989, according to the data.

Hartung was joined by Radha Natarajan, who is director of the New England Innocence Project and also represented Wright. According to the lawyers, Wright’s case is not unique. It was plagued by issues that have caused wrongful convictions in many other cases, including racial bias, misconduct by police and prosecutors, and “tunnel vision” by investigators, the lawyers said.

Hartung said that when Wright—“a Black man charged with killing a white woman”—was prosecuted, he “watched as every Black male juror was stricken from the pool” and “was forced to be seated away from his lawyer throughout the trial.”

“We know that what happened in Eddie Wright’s case … is part of a pattern of wrongful conviction cases, especially those involving Black men,” Hartung said. “In fact, police and prosecutorial misconduct played a role in 80 percent of wrongful convictions in murder cases involving Black men in Massachusetts.”

Natarajan pointed to a 2024 ruling by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, which found that the Hampden County District Attorney’s Office breached its legal duty to investigate allegations of misconduct by Springfield police officers and provide the information to defendants in criminal cases.

“This should not have been a fight at all,” Natarajan said. “Prosecutors should never protect and cover for police misconduct. … When prosecutors become aware of police corruption, … it should be their responsibility to identify all the other potential victims of that police corruption. It should not fall on individuals in prison or nonprofits like the New England Innocence Project to figure out who else was impacted by this official misconduct.”

Natarajan also called on legislators to update the state’s system for compensating victims of wrongful convictions. Under current state law, victims must file lawsuits, which generally take years to resolve, and compensation is limited to $1 million regardless of how many years the victim spent in prison.

“We know that no amount of money could make up for what Eddie has lost, but a $1 million cap is insulting,” Natarajan said. “It means that each day that he spent in a prison cell away from his loved ones is worth $66 to this Commonwealth, and we should be appalled by that.”

Proposed legislation would replace the litigation-based system with an administrative process that would have simpler eligibility requirements and be overseen by the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office. It would guarantee victims $115,000 per year of wrongful incarceration, compensation for time spent on parole, and an immediate $15,000 upon release from prison to help them transition from incarceration to freedom. It would also entitle victims to tuition waivers at state and community colleges, MassHealth insurance, housing assistance, and funding for a social-services advocate.

The legislation received a favorable report from the state legislature’s Joint Committee on the Judiciary in July. The bill is currently before the Senate Committee on Ways and Means.

Asked by a reporter why she thought the bill has a chance of passing this legislative session despite other compensation bills failing in recent years, Natarajan said that this proposal has the support of the Attorney General’s Office.

“It is the Attorney General’s Office who typically fights against these compensation claims,” Natarajan said. “But in this case, they are fighting for a change in the compensation laws. There is nobody who is opposing this. … This is the session where we can change things on compensation.”

“I’m Still Here”

When Wright was tried for killing his friend, the only evidence prosecutors used to link him to the scene of the crime at the time of the murder was a shoeprint with blood found in the victim’s apartment. The print, a prosecutor told the jury, was similar to the patterns on the sneakers Wright was wearing when he was arrested two days after the murder.

But prosecutors hid a report showing that police only noticed the shoeprint after someone who couldn’t have been Wright broke into the apartment and contaminated the crime scene. A detective also falsely told the jury that only police had access to the apartment while they were gathering the evidence.

“I went to trial thinking … that the truth was going to come out, that I would be exonerated, and that they would go after the guy that actually killed my friend,” Wright said. “I kept thinking, Okay, the lawyer is going to come out like Perry Mason, and he’s going to do his thing, and I’m going to be okay. That didn’t happen.”

During the years after Wright was convicted, lawyers gathered evidence that a different man confessed both to killing the victim and breaking into her apartment to steal items shortly after the murder. Although the Hampden County District Attorney’s Office possessed a report corroborating that the break-in occurred, prosecutors buried the document until 2021—36 years after Wright was convicted. It was this report that convinced a judge to overturn Wright’s conviction.

After the ruling, Hampden County District Attorney Anthony Gulluni dropped the charge against Wright. However, in a statement to the media, Gulluni claimed that the judge had overturned the case “based on procedural concerns” and said that Wright was nevertheless guilty. Gulluni said that because of “the significant passage of time and the loss of key witnesses,” a second trial was “not feasible.”

“The district attorney’s office continues to stand by the integrity of the outcome reached by the jury,” Gulluni said.

In response to a reporter’s question about whether “exoneration” was the correct term to use for the overturning of Wright’s conviction, Natarajan said: “Thankfully, the Hampden County district attorney doesn’t determine whether someone is exonerated. … If [prosecutors] wanted to stand by this conviction, they could have retried Mr. Wright, and they chose not to do so. … They’re not going to say that this is a conviction that has integrity. We know it doesn’t.”

According to Natarajan, “The case against Eddie, like so many others, involved tunnel vision—investigators zeroing in on him and developing a false narrative. They refused to let go of that narrative, even when evidence supported his innocence and another man’s guilt.”

Natarajan said that “false narratives often get solidified and spread through the media, and today, more than ever, we need people to question those false narratives coming from the government.”

“To protect us all,” she added, “we must truly embrace the presumption of innocence.”

During Wright’s four decades in prison, he filed six motions to overturn his conviction. Although the first five attempts failed, Wright said he learned new information each time.

“I knew if I was going to get out, I had to plan,” he said. “I took my time, spent the beginning of my sentence going to the law library, trying to learn the law.”

Wright said many of his loved ones died while he was in prison. He lost his mother, stepfather, brothers, sisters, cousins, and friends.

“I couldn’t go to the funerals,” he said. “I had to sit there in prison and just take it. … And over the course of time, it takes a toll on you.”

Wright said that throughout his ordeal, he was fighting not just to overturn his conviction but also with the Massachusetts Department of Correction.

“The Department of Corrections is another system that tries to beat you down, tries to take your humanity,” He said. “It does everything it can to break you, to make you want to give your life. Some people do. I watched a lot of guys who didn’t fight for themselves. They just got tired of being denied, and they just gave up.”

Wright said that no amount of money could ever make up for what was done to him and other wrongfully convicted people.

“I just want you to know that, with all those losses and all that I’ve went through, I’m still here,” he said.

“These Signs Are Human Beings”

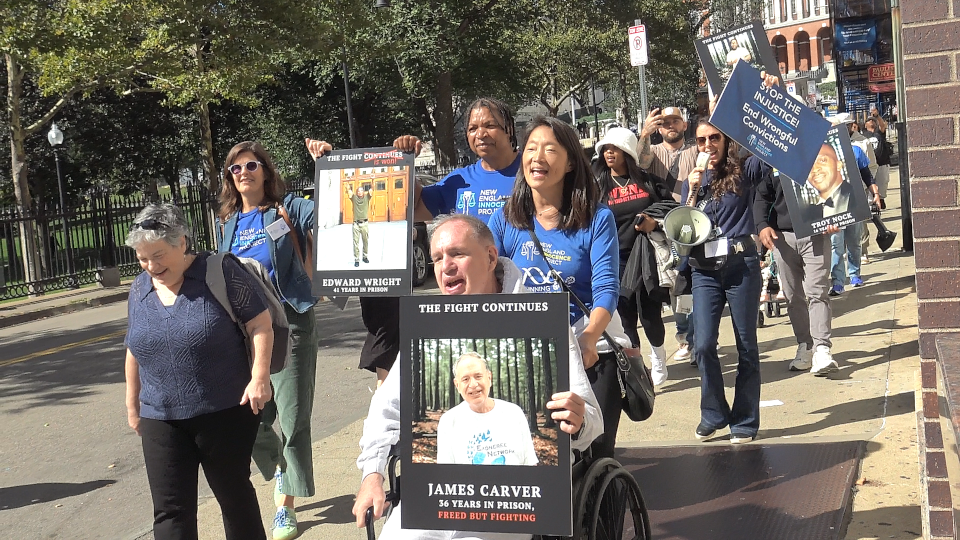

After the press conference outside the State House, Wright and other advocates marched to Boston City Hall, waving signs with photos of wrongfully convicted people who have been released from prison—and people who are still fighting to overturn their convictions from behind prison walls. As the advocates marched, they chanted to beats supplied by the percussion group Grooversity.

Outside city hall, the group was joined by state Representative Chris Worrell, one of the lawmakers who filed the bill to update the state’s system for compensating victims of wrongful convictions.

“Too often we see Black and Brown people being caught up in the system for something that they didn’t do,” Worrell said into a megaphone. “So when I think of wrongful conviction, I think of racist conviction. It must go. … And on Beacon Hill, you have an ally and supporter in me.”

Sean Ellis told the crowd that when people are wrongfully incarcerated, it affects not just them but their families and entire communities.

In 2015—after Ellis had spent 21 years incarcerated for a murder he said he did not commit—a judge overturned his conviction due to evidence of police misconduct. Ellis is now the director of the Exoneree Network, a group he co-founded to help other wrongfully convicted people after they are released from prison.

“One of the most important things that I’ll say to you today is: community, community community,” Ellis said. “When my mother was fighting for my freedom, she thought she was by herself. … This didn’t exist for her to tap into. What I want you to know is that even after today, this exists for you to tap into.”

Attorney Lisa Kavanaugh held a sign for one of her clients, Brian Peixoto, who is fighting to overturn his 1997 murder conviction. Kavanaugh directs the Innocence Program at the state’s public defender agency, the Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS).

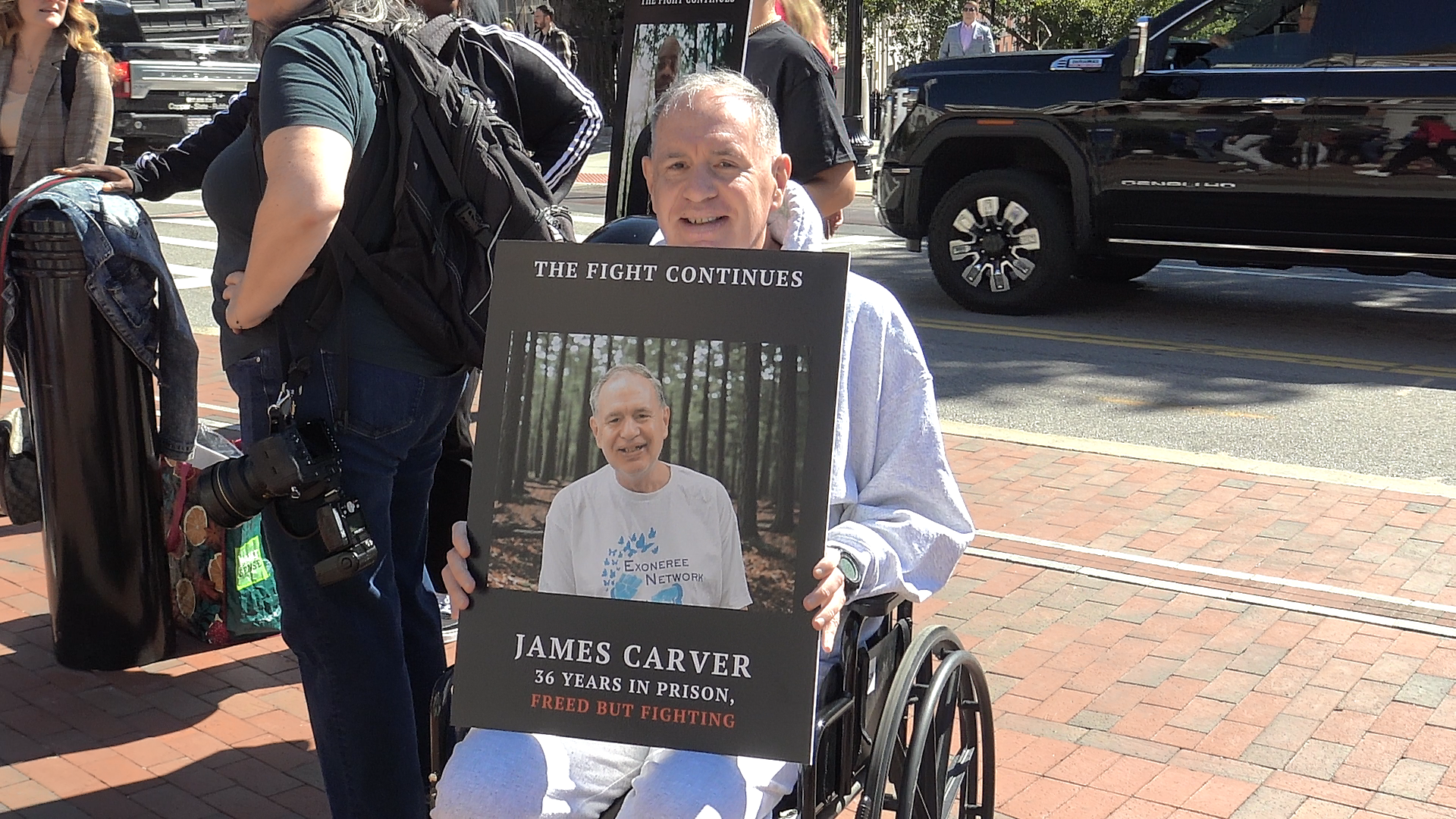

Kavanaugh said to cheers and applause that she was at the rally with another one of her clients, James Carver, who spent 36 years in prison on a life sentence. Carver was released from custody in February after a judge overturned his arson and murder convictions. The judge ruled that Carver is entitled to a new trial because prosecutors relied on junk science to show that a deadly 1984 fire was set using a flammable liquid and used unreliable eyewitness testimony to place Carver at the scene.

At the rally, Carver was seen petting another attendee’s dog and drinking an iced coffee from Dunkin’—two of the everyday pleasures he’s been able to experience since his release from prison that most people take for granted.

Carver, 61, requires a wheelchair to get around due to a 2005 surgery to remove a brain tumor. He attended the rally with a CPCS social worker, who pushed his wheelchair during the march. Throughout the day, he held a sign with his picture on it. The sign said “THE FIGHT CONTINUES” and “FREED BUT FIGHTING.”

The Essex County District Attorney’s Office is appealing the judge’s ruling that overturned Carver’s convictions. In a brief filed in September, prosecutors argued that the judge abused his discretion by tossing the convictions because other evidence points to Carver’s guilt. Due to the appeal, Carver is not currently eligible to sue the state for compensation.

Kavanaugh told the crowd that people “need to care about wrongful convictions, not just today, but every single day.”

“And we need to bring these stories to people who aren’t hearing them,” she added. “These signs are human beings. They’re human beings who our community, our society, our court system, has put in cages, many of them sentenced to die in prison. And we have a responsibility to lift up their voices, to lift up their signs, to bring them with us every year until we free them all.”

On a related note, I recently appeared on BINJ Live to discuss wrongful convictions in Massachusetts. You can watch that here:

Anyway, thanks for reading! Journalism like this takes a ton of time, energy, and care. If you’d like to keep The Mass Dump running, please consider offering your financial support, either by signing up for a paid subscription to this newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo. I rely on your support to keep doing this work, and a monthly subscription is just $5!

Even if you can’t afford a paid sub, please sign up for a free one to get updates about this story, and please share this article on social media.

You can follow me on Bluesky and Mastodon. You can email me at aquemere0@gmail.com.

That’s all for now!